back

to book details

buy the book

excerpt

reviews

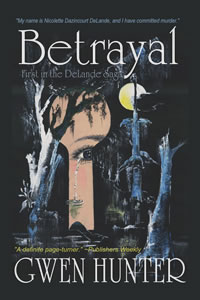

BETRAYAL

PROLOGUE

My name is Nicolette Dazincourt DeLande, and I have committed murder.

How

do you synopsize a life, I wonder, cut it back and down, hacking into

it like an untamed wisteria, rampant with lavender blooms, tendrils all

coiled around and choking. How do you trim and clip the lush foliage of

a life, making it docile and compliant, conformed to a foreign shape and

structure. What kind of life is that... colorless and staid, to fit a

mold of another's making. Yet . . .

Do you have any idea what a southern girl

is taught to do? Not a big city girl, but a girl from Cajun country, a

girl from the swamps, south and west of New Orleans, just off the Atchafalaya

River. My daddy was a veterinarian, and not a rich one either. So by the

time I was twelve I was equally proficient with Daddy's shotgun and Mama's

old Zig Zag Singer. I could embroider, run a trot-line—a catfish

line—gig for frogs, crochet an afghan, spin-cast for bass, and handle

the vet clinic in a pinch. I could splint a dog's broken leg, weigh him

and dose him with morphine to hold him till Daddy got back, make Xrays,

birth puppies, kittens, or pigs, perform the Heimlich maneuver or CPR

on a choking or electrocuted pet, put a damaged one to sleep, calm the

owners, collect the fee, and send them away satisfied. I could play the

flute, which I hated, draw, write bad poetry, speak passable French, sing

in the church choir, and cuss fluently, albeit under my breath and never

out loud. I could do all that. And it was a damn good thing.

I met Montgomery Beauregard DeLande when

I was still a gawky teenager, climbing trees and playing Tarzan and Jane

and army. He was tall, and redheaded, with blue eyes and a lanky frame

that captivated all the girls in Moisson. He had a knife scar over his

right eye and another that marked his collarbone. It peeked out, along

with a tuft of curly red chest hair, whenever he was playing soft ball,

or working with Henri Thibodeaux bent over the hood of a restored antique

Ford. And he had a smile that would light up a dark room better than the

finest crystal chandelier.

Montgomery

was an older man. Twenty two if he was a day. He was one of the DeLande

boys from Vacherie, a town halfway to New Orleans. And God knows I would

have given my soul to have him just look at me once. I almost did. I may

have.

Chapter One

Life

never was easy in south Louisiana, except for those wealthy enough to

make the choices and purchases that changed the lifestyle. My daddy wasn't

one of the lucky ones born to wealth and prominent social position. And

the fortune he'd hoped to make with the oil boom of the early seventies

died along with his investments and the family reputation, sinking into

the mire of the Louisiana landscape. Oh, we never did without. We always

had plenty to eat, even if it was pulled or netted from the freshwater

Grand Lake Swamp or the river basin. And we always had enough to wear,

even though it was only copied from a fashion magazine and sewed together

on Mama's worn-out Singer.

We lived in a little town called Moisson,

near Loreauville, Louisiana, inside the Atchafalaya River Basin. Baton

Rouge was northeast, a good two-hour drive for those with the car, the

gas, and the inklin' to travel. New Orleans was due east, with its multiple

societies and closed social order. But no one I knew belonged to either

the courtly, aristocratic society or the swarms of the debauched, roaming

the streets of the French Quarter seeking thrills by night.

When I was twelve Mama came into her inheritance,

and thereafter we spent each hot July in New Orleans, soaking up the culture

Daddy had in mind for me to marry into. Mama was a Ferronaire, of the

New Orleans Ferronaires, and had married beneath herself both financially

and socially when a Dazincourt wooed and won her at one of the "white

gown balls" for the socially prominent during Carnival the year she

made her debut. Of course, the Ferronaires always married beneath themselves,

everyone else being inferior.

Nonetheless, she and Daddy wanted something

better for me than Moisson offered, so each July Mama, my best friend,

Sonja, and I ate in fine restaurants, experienced opera in the Theatre

for the Performing Arts, and plays in the La Petit Theater du Vieux Carre'

and the Theater Marigny, heard the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra in

the Saenger Theatre, and jazz in Tipitina's, the Maple Leaf, Muddy Waters,

the Absinthe Bar, and Tyler's.

We toured horse-breeding farms for New Orleans'

Thoroughbred Racing, and the Fairground Race Track even though it was

off season, trading on the Ferronaire name and Ferronaire connections.

And we visited fashion houses, where Mama looked, studied, and mentally

stored designs for the coming year. She was talented with cloth and needle

like no one else. If she'd been a stronger woman, she'd have bucked Daddy

and opened a shop. But maybe she liked the solitude of Moisson and her

dependence on him.

Moisson had society of a sort. Local dances

and church picnics and hay rides in the cooler weather of what passed

for fall. But the concept of high society was beyond us all. Designer

gowns and the private Carnival balls during Mardi Gras simply were not

a part of our growing up. Without school, I would never have had the opportunity

to meet the types of people who fit into polite society. And I certainly

would not have met the types of people who didn't fit into society at

all.

I attended the Our Lady of Grace Catholic

School in Plaisant Parish from the time I turned nine and Daddy decided

I might someday become a beauty. It was his hope that I would attract

the kind of man who could lift the family back up into its proper social

and economic stratum. In other words, it was his intention to sell me

on the marriage market to the highest bidder. Ferronaire connections would

admit me to the debutante balls and the Carnival "white gown balls"

of Mardi Gras. The rest would be up to me and the training I received

at Our Lady.

It was because of Our Lady of Grace that

I met both Montgomery and Sonja. It is ironic that the sisters gave me

both my damnation and my savior. I was ten when Sonja LeBleu first came

to Plaisant Parish. She was beautiful; a dark-eyed innocent wanton with

long, tapering fingers and beguiling eyelashes and a natural grace that

put all the girls at Our Lady to shame when it came time to learn the

dance steps popular in Creole ball-rooms.

I was surprised that Daddy let me learn

to dance. A stern eyed closet Pentecostal in Catholic camouflage, he preached

the danger of dancing, dating, sex, and sin most evenings at family Bible

study. But that was before I understood about the marriage market and

Daddy's designs on my future.

Sonja seemed born to dance. Her feet would

learn the steps and her body would move into the proper forms as though

she had already known what to do and had simply waited for permission

to start. I wasn't half so lucky. Too tall for my years, and clumsy by

nature, I had as much trouble learning to dance as I did learning to speak

the Parisian French we studied three times a week. In both classes, Sonja

outshone us all. And if she hadn't been a worse outcast than I, we probably

would never have become friends.

Sonja was the lowest of the low in Louisiana

society. One step below mixed-blood Indians or white Cajuns, French persons

with black blood in their lineage were considered outcasts. Practically

untouchable. Called "high yellow", and "coon-ass",

they had no chance to advance in proper society - unless they were beautiful

and accomplished. Sonja was going to become both, move to New York, and

pass for cultured but impoverished gentry. Passe' blanc. Pass for

white. Yankees, unfamiliar with the class strata so long established in

the South, would not recognize nor care about Sonja's heritage, and she

could make a good marriage into good green Yankee money. Or so the reasoning

went.

Montgomery came to town the year I turned

fourteen. I was too tall, too thin, and still suffering - as only the

young can suffer - the continuing disgrace of the family name. My Uncle

John Dazincourt had been disbarred for graft (the monies involved being

over and beyond the expected norm for a Louisiana politician) in a well

publicized courtroom scene only the year before. As he was the second

Dazincourt uncle to be publicly discredited in recent years, the shame

would have been unbearable but for Sonja. She just smiled her secretive

smile, patted the back of my hand, and silently stood by me, waiting out

the scandal. Even then, Sonja knew when to speak up and when to hold her

peace.

Early that spring, as the scandal was at

its peak, Sonja and I were eating lunch together on the school grounds

of Our Lady, our plaid uniform skirts tucked beneath us, napkins spread

across our knees, sitting apart from the other girls in their little knots

all a-whisper. Closest to the pitted road, we had just finished our sandwiches

and pears, and were wiping our fingers delicately on our napkins when

a motor sounded in the distance. A dirt streaked antique Ford, its engine

loud but smooth, pulled down the road and braked, showering Sonja and

me with a fine powder.

A red haired, blue eyed man, his teeth strangely

white in his dust streaked face, braced an arm against the open window

and leaned out the car. His eyes fell on Sonja, and as always with the

men of Moisson, they stayed there.

"Excuse me, miss. Could you direct

me to Henri Thibodeaux's place? I seem to have made a wrong turn somewhere."

The engine roar covered all the sound from

the garden, but I could well imagine the giggles and whispers. The sisters

had often told us never to talk to strange men, certainly not strange,

dusty, gorgeous men leaning out of expensive classic cars, looking at

us like he was. Like a fox at bait. But they had also told us to use our

manners. And ignoring the stranger's question and his obvious adversity

was not the way to handle this situation.

I was tongue-tied as usual. But Sonja, her

lashes downcast against the dust, smiled and directed the man to the front

door and Sister Ruth, who stood there watching, her eyes like dark thunder

clouds. The man tipped his hat - a curiously old fashioned gesture - put

the auto into reverse, and backed up the drive. Distinctly uncomfortable

and red of face, Sonja and I retreated to the coolness of the classroom

and the giggles of our classmates.

Later that afternoon, Sister Ruth came into

the dancing classroom and interrupted. It seemed Sonja had responded in

the correct manner when she sent the charming gentleman to the front door

instead of answering his query herself. Sister Ruth, her black eyes sparkling,

praised Sonja, and by proximity, me. It wasn't exactly the sort of tongue

lashing Annabella Corbello had envisioned for us. It seemed the red haired

man had charmed even dour Sister Ruth - no small feat. But that was Montgomery.

He could charm the bark off a live oak.

From the first moment I saw him, he enveloped

my life, taking over the secret, intimate places where dreams nest in

the heart of every young girl. Romance and passion bloom in these dark,

moist havens, fantasies of rescue and stolen kisses, declarations of love

and fidelity ever after, fantasies nourished by writers like Devereax

and Lindsey and countless others who fuel the romantic expectations of

this generation of women. These fancies would overtake me at the strangest

times. I'd be working in the back of Daddy's veterinary clinic, washing

out the pens of the few overnighters or post-surgical patients, and in

would stride my imaginary Montgomery. Taking the hose pipe (that's southern

for garden hose) out of my hand, he'd sweep me off my feet and carry me

out of there, just like Richard Gere in An Officer and a Gentleman.

Or so a typical daydream would go.

Of course, in real life the puppy poop and

kitty vomit would have made walking precarious, breathing difficult, and

romance impossible. But reality has little to do with the pirated dreams

of a young girl. Montgomery became my life. I even took over the crabbing

and cat-fishing from my brothers just so I could motor Daddy's flat-bottomed

boat or the pirogue through the lakes and swamps and tributaries of the

Atchafalaya River Basin towards Henri Thibodeaux's place in the faint

hope that I'd get a glimpse of him working in the yard on the vintage

autos the two men loved. I never got lucky.

Daddy, however, was pleased to see that

I was making use of all his training, that I hadn't forgotten the swamp

lore I learned at his knee. At least I made one man happy.

I had better luck in town, spotting Montgomery

at local dances, escorting one of the parish's young beauties, dancing

and sipping punch. I saw him at church for mass, and twice at confession.

I went regularly on the same day at the same time thereafter, hoping to

see him again. I saw him at the store buying bottles of liquor for one

of the parties he and Henri Thibodeaux threw for the parish's young, wild,

and rebellious set.

And I asked around. I learned all about

this red-haired man with such uncommonly refined manners. He charmed everyone

he met, from the parish priest, Father Joseph, to the man who swept out

Therriot's grocery store. And I don't think he ever noticed me. Not once.

But when I turned sixteen, things changed.

I changed. One day I passed the tall gilt mirror in the entryway and stopped,

frozen. Because the reflection wasn't me. It was Daddy's vision of me.

And I was almost afraid of going back and getting a better look. But I

did. And oh, God, I was fine.

Tall, yes, but in the way Glamour magazine

called willowy, with long legs and a slim frame, and graceful as a ballerina.

My face was delicately boned, with golden skin and gray eyes turned up

at the corners - sloe eyes, they called them - and ash brown hair that

was a riot of curls from the moist heat of August. I knew in that moment

that my dreams could be reality. I could have Montgomery DeLande. I could.

And I would.

Ten months later I graduated from Our Lady

of Grace in a white-glove-and-lace-dress-ceremony. Montgomery was in the

audience. I knew, because Henri Thibodeaux's sister Anne was graduating,

too, and it was common knowledge that she expected a proposal from Montgomery

any day now.

But I knew different. The Montgomery of

my dreams would never settle for some hoyden who would jump between the

sheets with anyone who caught her fancy. Montgomery DeLande would only

settle for the best. The finest. The most pure.

Thanks to my daydreams and the fact that

no local boy had ever measured up to the perfection I ascribed to Montgomery,

I was all those things. Pure and unsullied and ripe for the man with the

patience and the skill to win me.

That night began our courtship. That night

set me on the road to hell.

Montgomery

and I were engaged on New Year's Day the year I turned eighteen. If a

new cedar shake roof on the 150 year old tidewater house I'd grown up

in seemed a strange way to seal an engagement, no one mentioned it to

me. And Daddy was ecstatic. His new son-in-law-to-be was all he'd ever

envisioned. A man's man who could fish and hunt and restore a classic

car as well as any man in the parish. And he had money. Lots of money.

Money he was investing nearby in Iberia Parish in the new Grand Lake Resort.

Money he wanted to invest in Moisson. Money he settled on Daddy and Mama

in a financial arrangement that was never discussed with me.

I married Montgomery when I was twenty and

had my first baby that same year, my second the next year, and my third

before I was twenty five. But long before my wedding day we were lovers.

Sex wasn't at all what I had thought it

would be. Oh, at first it was a slow-building passion and the thrill of

discovery. But later it became a frenzy and a fury, like a late summer

storm from the gulf, drenching and violent. And after it was over, a desultory

heat and a feeling of incompleteness.

Passion and desire were a part of my nature,

built into my genetic code like the sultry heat of a moist night. There's

something about southeast Louisiana and what it does to people. The awful

wet heat and the rain and the smell of rich earth bring all the basic

hidden needs out, close to the surface, so that passion and desire, obsession

and rage, are intermingled and primed to a fever pitch. Always.

My honeymoon was a romantic week in the

States and ten whirlwind days in Paris, France. We flew back to New Orleans

on the Concorde—me drinking champagne till I was too tipsy to walk

straight. As though he expected me to mutate into something strange and

alien under the effects of the alcohol, Montgomery watched me with intense

eyes. Eyes brooding and heavy with passion. Unaccustomed to the wine,

I simply giggled, and Montgomery had to support me through the terminal

to the waiting limo, where he poured me still more champagne.

It was a vintage limo, one that had been

in the family since the sixties, and had been used in the funeral procession

for President Kennedy. Silver gray with rounded windows and leather interior,

it lacked the modern conveniences of today's models, but it made up for

the deficiencies in sheer luxury. As though he were starved, as though

we hadn't made love in our Paris suite for most of the night, as though

the driver didn't know what we were doing behind the closed privacy screen,

Montgomery pulled away my clothes and made love to me on the drive out

of the city. Over his shoulder, I watched New Orleans slide away.

The limo drove us through the sweltering

city and into the countryside, through oak-lined streets heavy with moss

and signs of marsh and age, for the final honeymoon weekend near Vacherie.

Miles from that small town, we stopped in front of a two-hundred-year-old

mansion with a two-story wraparound veranda and what looked like a family

crest emblazoned on the front door - a bird of prey with bloodied talons.

A wisteria grew up beside the front door,

a beautiful plant with fragrant blooms hanging down and buzzing with bees.

The vine was the only foliage not pruned and clipped and shaped into balance

with the other vegetation. Instead, it had been allowed to grow wild for

years, wrapping its thin, wiry arms around the massive trunk and branches

of its host tree. Almost lovingly it had encircled the tall timber, slowly

strangling the massive trunk and branches with ever tightening arms, till

it choked the life out of the old oak. A slow graphic of life and death

both sensuous and cruel, the vine ran in long, spidery ropes across the

ground, up the trellis, and over the circular porch at the corner of the

house, as though if left to its own, it would eventually devour the house

and grounds. As though some demented gardener had set it loose to consume

the place. It was vicious and savage. I have always loved wisteria, especially

this wild one.

Though Montgomery had not told me our destination,

I knew where we were. I had been waiting for this part of our honeymoon,

and I stared out through the darkened windows at the sculptured grounds.

Shrunken from its once glorious past, the DeLande Estate was now five

hundred acres of pecan groves, fallow fields, and horse-breeding barns

for the DeLande racing stock. One of the few showplace homes spared from

the burning ravages ending the Civil War, it was still kept entirely for

the personal use of the founding family.

Unhurried, Montgomery helped me back into

my clothes, smoothing the wrinkles with a practiced hand, his eyes once

again sharp and scowling. "Come on, Montgomery. I'll be on my best

behavior. I promise your family will like me."

He stared at me with an unreadable expression,

his mouth tightening, and turned away, opening the door into the cooler

air of the country. "That isn't my concern," he said. "My

concern is that they'll like you too much."

Puzzling over that cryptic comment, I buckled

my belt and slipped on my shoes, knowing I had angered him somehow, but

determined not to show I cared. I wouldn't start out my marriage being

intimidated. I would not become my mother. I wouldn't.

My father was a strong man in both personality

and physique. Overbearing at times. Yet many women would have figured

out how to live with the man and still conserve dreams and ambition of

their own. They would have learned how to assert their own personalities

into the home, while still keeping his love. I know. I had done it. The

heroines in the books I read did it all the time. But my mother never

had.

I smoothed the final wrinkles out of the

dress we had picked up in Paris and smiled brightly at Montgomery. He

glowered back.

While the driver unloaded the mountain of

bags, Montgomery took my elbow and escorted me inside, introducing me

to the house, a legendary place of long, cool hallways and twelve foot

ceilings, rich with family heirlooms, old rugs, and priceless art. It

was a strange house, unbalanced and unnerving in the eccentric juxtaposition

of furnishings. Seeming to loosen up as we walked the cool, dark hallways,

Montgomery pointed out the family treasures.

There were twenty-six tall-backed Frank

Lloyd Wright chairs grouped around an ornate Louis XIV table in the dining

room, and a collection of antique swords against the wall over the table.

The steel had been sharpened and polished till it looked like it was used

every day, yet was protected from the damage of pollution and damp by

a locked glass door.

On the opposite wall was a glass fronted,

modern Scandinavian armoire twenty feet long and eleven feet high holding

elegant Oriental vases and two-hundred-year-old china, still used by the

family. The walls were painted matte black, textured with a sponge dipped

in dark green enamel. A dark green coated the moldings, and matching green

drapes fell twelve feet from the ceiling to puddle on the dark wood flooring.

It should have been a dark room, but one whole wall had been knocked out

for French doors which let in the afternoon light.

Worn Aubusson rugs covered the floors, and

every room housed collections. On the parlor walls hung a collection of

Picasso drawings, the modern shapes standing in sharp contrast to the

antique furniture; in the music room were two Monets and a grouping of

violins, an old Steinway - out of tune - and upholstered Art Deco chairs.

Styles, periods, and colors were mixed and matched in odd combinations,

with the cool dark green shade of the enamel flowing through the house

like deep water, pulling the whole together.

We toured only the downstairs of the main

wing, but already I understood that the DeLandes were a far richer family

than even the Ferronaires. I wondered what Montgomery could possibly have

wanted with me when he could have married into more wealth.

Nine of the DeLande children, several of

their wives, and a round dozen grandchildren were waiting for us in the

gathering room at the back of the main house. The walls of the room were

mounted with deer heads and a Louisiana panther, endangered for decades.

Snowy egrets with wings spread, or nesting with their young, and snakeskins

moldered on the walls and shelves, ancient trophies of blood sport. And

everywhere birds of prey. Horned owls and a half dozen eagles, some now

endangered, barn owls and falcons and hawks, all high on a shelf that

circled the room above the French windows. All were dusty and neglected.

Some looked generations old, and I remembered the crest-like plaque on

the front door - a bird of prey with bloodied talons.

Faded, deeply upholstered chairs and sofas

sat side by side with austere hard-wood benches, small tables—marked

with numerous rings and small cigarette and cigar burns—at their

arms. Even with the tall ceilings, this room was close and intimate, intense

with DeLande personalities and DeLande judgment.

They sat on one end of the room as if our

appearance in the doorway had interrupted an informal conference. Staring,

they looked us over, evaluating, calculating, all gathered around the

Grande Dame DeLande, the faded beauty whispered about over half a state

for over half a century. I stared back unashamedly. She was still a striking

woman, black-eyed and pale-skinned, with long silver hair twisted through

with a strand of pearls. Pearl enamel earrings heavy with gold pulled

at her lobes, and on her left hand was a plain gold band and an monstrous

emerald ring. She was dressed for dinner in emerald silk. All this I absorbed

slowly, feeling the silence of the collected DeLandes as they studied

me.

The rumors of this dark-eyed siren were

numerous, most of them shadowy and twisted, with one similar, overriding

component. That the last baby, Miles Justin, was not the direct offspring

of Monsieur DeLande, but had instead been sired by one of his own sons

in an incestuous relationship with the Grande Dame. That the Grande Dame,

called that even then, had cuckolded the old man by sleeping with one

of her own sons and conceived a child. And laughed about it to his face.

Enraged, Monsieur DeLande had tried to kill

her and had instead been gunned down by one of his boys. The oldest at

the time was seventeen. The Grande Dame had falsely confessed to killing

her husband, but had never been charged, such was the power of the DeLande

name. And no one knew which of her sons had fathered the baby or killed

the old man. Or so one set of rumors went.

Another set painted her the heroine, saving

one of her sons from death by shooting her husband when he went berserk

and attacked the gathered family with a hunting knife. According to the

proponents of this scenario, DeLande had been cuckolded, but by his own

brother.

I was without opinion about the rumors and

without the necessary daring to ask Montgomery for the truth. I was also

young, foolhardy, and careless, confident in my own sagacity, unaware

that I had little. I wrenched my eyes from hers, seeing in their depths

that she read my thoughts and was amused, and perhaps a little angry.

Into the silence Montgomery spoke. "Nicolette

Dazincourt DeLande. My wife." The accent on the last two words was

challenging, defiant, and his jaw was outthrust as he stared at the assembled

grouping. I had accepted his reasons for the absence of his family at

our wedding, but hearing his tone now, I wondered.

The room was silent for a long moment following

Montgomery's announcement. Then one brother began clapping, slowly and

distinctly, though whether it was for me or for Montgomery's statement,

I never knew. Unwinding his long, lanky body from the seat of a straight-backed

wooden chair, he stepped forward, his teenaged face intent and half smiling,

scuffed boots striking the wood flooring.

Taking my hand, he bent his lips to my fingertips

in a gesture that would have been absurd in anyone else. Cocking his head,

he smiled and said gently, "Miles Justin. The peacemaker." I

had a feeling there was laughter in the depths of his black eyes, laughter

that made the scene of greeting farcical. I smiled back at him, relieved.

A second brother, still seated, nodded,

green eyes bright. "Andreu. The Eldest." It sounded like a statement

of explanation or title, as though I should derive some special meaning

from the words.

Another tilted his head, "Richard."

Shorter and heavier than the rest of the men, he had nondescript eyes,

neither blue nor green, but hard and unreadable.

A man with a rakish smile stepped up to

me, pushing Miles out of the way with a rough movement, and pulled me

into his arms, kissing me on the lips, hard. His eyes were on Montgomery

over my head, and he laughed low, like a growl, as he released me. "Welcome

home, little sister. I'm Marcus."

Montgomery stiffened beside me, and one

of the sisters hissed. I thought it was Angelica, Montgomery's favorite

sister, the only redheaded female in the bunch. Whoever it was, the sound

released some hidden tension in the room and everyone laughed, approaching

me en masse, for hugs and kisses and a closer look.

Cold and distant, or warm to the point of

impropriety, Montgomery's strange family greeted me, while the Grande

Dame merely watched, her eyes cool as her smile. My new husband finally

led me forward and presented me to her. I could smell the scent of perfume

as she lifted her right hand. But instead of shaking my hand as I thought

she intended, she merely twirled her index finger slowly as a silent command

for me to turn around so she might view me from every angle like a rare

vase she might buy. Her dark eyes glittering, she smiled at Montgomery,

and he nodded in return. But it was more than simple acceptance, and the

hairs rose slowly on the backs of my arms.

I felt fortunate when the butler announced

dinner before the feeling could worsen, and we moved together toward the

dining room, the Grande Dame on my left, Montgomery on my right. Miles

Justin moved to pull out my chair, his smile wry and mellow, mature for

his years. He couldn't have been more than fourteen.

The long stretch of table served us all

comfortably, the youngest grandchildren having been carted off screaming

to eat in the kitchen, as the sun set and cast shadows and prisms of light

across the setting. Servants, quiet and elegant in dark jackets, moved

discreetly in the dim corners of the room.

The conversation was purely southern, with

a light smattering of horses, farming, the world economic picture, and

a heavy dose of politics. Yet I seemed to fit in only when I was silent,

though I knew a bit about horses and offered an optional course of treatment

for a breeding mare with digestive problems. Only Miles Justin bothered

to respond, asking for the recipe of the bran mash Daddy used to treat

Mr. Guidry's delicate little Paso Fino.

After the "light dinner"—a

sumptuous affair with six courses—the family retired back to the

Gathering Room. Here I was silent, aware of Montgomery's increasing agitation.

Members of the family came and went in singles and pairs, the Grande Dame

the only one who was stable, never moving from her chair, her eyes following

each movement, settling often on me and on Montgomery, who seemed to flinch

each time he caught her watching him.

Twice when her eyes met mine I glared back, and

this seemed to amuse her, but she acknowledged the expression each time

with a slight nod. Late into the evening, long after the day's wine had

faded, and long after the novelty of this complex and unpleasant family

had worn off, the Grande Dame signaled to me. "Come here."

I don't know how she did it. She didn't speak; she didn't motion. But

I knew I was being bid forward.

I came and sank onto a cushion at her feet.

There were dozens of these cushions strewn around the room, tassels loose

and twisted or molting with age, all made from the same ancient and brown

stained Aubusson rug. I chose one with pale roses and gold tassels, fingering

the fringe while this woman stared at me, and the remembered feeling of

the afternoon returned. The hairs quivered along my arms and on my neck

beneath my hair.

"You're breeding." It was the

kind of thing a member of royalty might say to the lightskirt parlor maid

just before she was dismissed. Scornful and contemptuous. I swallowed,

because I had told no one except Sonja, and Montgomery had instructed

me to remain silent about the fact to his family. Obviously he had decided

to tell his mother, and she wasn't happy about it.

"No. He didn't tell me," she said,

correctly divining my thoughts. "My family has a bit of the mystic

about it. Sometimes we know things." She smiled at last, a real smile,

the one that had ruled the Carnival Balls in New Orleans for forty years,

and I understood how she had won the power she now wielded in the lower

part of the state. When she smiled this smile, she sparkled, like a black

opal with fire at its heart. "When are you due?"

Feeling it was useless to contradict with

a lie I knew somehow she would see right through, I said with all the

dignity I could muster, "In seven months."

"Did my son marry you because you're

carrying his brat?"

The insult was asked casually, as though

it were not a foul slander; as though I should answer calmly. Instead,

shaking with the temper I have fought all my life to control, I stood.

Looking down on her, I said softly, "Your son and I have been engaged

for two years. You were invited to the wedding. This baby was planned.

I tell you this now because obviously you... he... told you nothing about

me till the moment I walked in the door. I am not some floozy who trapped

him into marriage."

Instead of responding to the tirade, she

laughed at me, a tinkling sound. "Floozy. I like that word. Haven't

heard anyone use it in years. No, you are not a guttersnipe. Lineage?"

"Dazincourt and Ferronaire." I

knew she could read the anger in my eyes, but she chose to ignore it.

"Oh yes. The Ferronaire scandal. I

recall when your mother ran away and married so far beneath her. But your

father was a handsome man and many envied her. Myself included. You'll

do. Tell my son he can relax. He's been as jumpy as a whore in a queen's

bed all night."

I knew I was dismissed. Montgomery, who

was standing right behind me and had heard every word, took my elbow and

led me away. We went down two long hallways, one running the length of

the main house, the other intersecting it near the kitchens, to our rooms.

Montgomery's hand was so tight on my elbow that the feeling faded from

my fingers and sharp runnels of pain traveled up my arm. I lost my way

after the second turning, but Montgomery never faltered, his pace increasing

as he strode, pulling me along an unlit stairway and left, down a final

hallway to the lighted room at the end.

It was a sumptuous suite done in forest

green and French Country antiques, which under other circumstances I would

have paused to admire, but I was angry. So angry I was shaking.

Our bags had been unpacked, our nightclothes

laid out in some old world kind of service, and Montgomery slammed the

door behind us. Dropping my arm as though it burned him to touch my skin,

he went straight to the bathroom. Seething, I followed.

"How could you? How could you not tell

them? How could you not warn me?" He carefully squeezed out toothpaste,

loading his brush, the water shooting so hard into the porcelain sink,

it splattered onto the mirror above. "You never even invited them

to the wedding, did you? Montgomery? Are you listening to me?" I

jerked his wrist, knocking the brush from his hand, pulling him around

to look at me.

His eyes were blazing with anger and with

something else. Fear? I turned away quickly, shaking, turning off the

jet of water and cleaning up the smear of toothpaste. He closed his arms

around me from behind and laughed, a hysterical sound. His arms tightening

cruelly around me, he pulled me back to the bedroom and onto the bed,

taking me with a brutal ferocity. Frightened, I let him do as he wanted,

not protesting even when he hurt me, plunging into me dry and unprepared.

In the books I read, those romance novels

of undying love, sex always put a man into an expansive mood, made him

smile and try to make up. But Montgomery lapsed into a depressed silence

and uneasy sleep, and I feared to move, not closing my eyes till after

midnight.

During the night I woke, perhaps hearing

some sound, some echo, some ambient breath or rhythm alien to this place,

to find two figures at the foot of the bed. I gasped, grabbing for the

covers which had somehow reached my feet, pulling the sheets up over my

breasts. Richard and Marcus stood there, watching me, and I flushed in

the darkness, because I had fallen asleep naked, pinned under Montgomery's

arm after the brutal intimacy of sex.

Marcus held out his hand to me and seemed

surprised when I shrank back against the pillows. Some moments later,

they turned and left, closing the door silently behind them. Beside me

Montgomery's eyes glittered in the night, and I had the uncanny feeling

he blamed me for the presence of his brothers in our room. Without a word,

he rolled over and shut me out. I pulled on the nightgown I hadn't had

time for earlier and fell back into troubled dreams.

Montgomery never answered my questions.

When I brought up the subject of his family the next morning, he walked

out the door, locking it behind him. I hadn't noticed the odd locking

system on the door when we came up the night before, but it could be locked

from the inside or from the outside, the choice of the one who held the

key. Why hadn't he locked his brothers out last night?

Through the bedroom windows I watched the

family gather on the back patio for breakfast, seeming like a solemn group,

though I couldn't hear their voices. The Grande Dame was seated at the

table nearest the French doors, which I realized were the same French

doors of the dining room. Montgomery joined them, moving fluidly through

the throng to the buffet and serving himself. He sat with a group of girls,

and Miles Justin joined them, tossing a leg carelessly over the back of

the chair as he sat, his denim-clad torso and boots standing out in the

crowd of casually but elegantly dressed people.

I watched as my stomach growled and my breath

fogged the window with anger. I watched as the crowd grew and as it thinned.

I watched as the Grande Dame summoned Montgomery and Miles. I watched

as Marcus approached and the men seemed to become angry, their body movements

stiff and tight. I thought they might fight. I watched as the entire family

moved away to the left and around a corner, leaving the cluttered tables

for a small army of servants to clean. Then I found a chair and simmered,

wondering if the entire episode had something to do with the visitation

during the night.

Later that morning, Montgomery returned,

carrying a tray in his right hand, and holding a bloodied piece of linen

and lace against his neck with the other. He kicked the door closed, locked

it with his left hand, leaving a smear of blood on the varnished wood.

Grinning, he approached me with that panther's grace that all the DeLande

men seemed to possess.

My eyes focused on the blood, which seeped

past the frivolous piece of cloth and down his shirt. "Montgomery?"

All the anger and seething of the solitary morning leached away at the

sight of his blood pooling on his collar.

"Yes, my lady?" His voice sounded

jaunty, full of life and eagerness, teasing me as he had when we were

courting. His eyes were bright, animated. "Is my lady hungry?"

I took the tray, put it on the table by

the windows, and stopped, uncertain.

"Well? Aren't you going to patch me

up? Or did I wait through two years of nursing school to marry you for

nothing?" His right arm clasped me around the waist and twirled me

around the room as the blood flowed down into his shirt and stained my

skin through our clothes. It was bright and sticky, and I couldn't take

my eyes from it.

"Come on, beautiful wife. Do your duty

and act as surgeon to your injured husband." He kissed me, his lips

soft as they moved over my skin.

"What happened?" My voice was

hoarse, and I cleared it.

"Cut myself shaving."

I almost laughed. It was the DeLande charm

and I wanted to strangle him for it, fighting to keep all the anger I

needed at hand. But he danced me toward the bathroom, mumbling something

about Steri Strips and hydrogen peroxide against the skin of my throat.

He was almost giddy when he pressed me finally

against the cool of the sink, and I steeled myself as I reached out and

pulled the handkerchief away.

It was a knife wound about three inches

long, and deep, stopping only because the blade had hit his collarbone.

If it had gone higher an eighth of an inch, it would have slipped past

the protection of bone and bitten deep into his neck, into his external

jugular. The blood-smeared skin pulsed with the carotid, just beyond.

I swallowed and applied pressure with shaking

fingers, searching the medicine chest for the supplies he had mentioned.

They were there, along with clear, inch-wide tape like hospitals use to

hold IVs and gauze in place on the human body. All the while his hands,

now free from holding the cut, ran up and down my body, smearing the blood

into my clothes and hair and skin, pulling at me and at my clothes, sticking

as the blood became tacky. He mumbled as though drunk against my skin,

making my job difficult, but I finally got the wound clean and dripped

on the hydrogen peroxide. It bubbled deep and Montgomery gasped, biting

into my neck and knocking loose the gauze I held.

"Stop it. I need to get this cleaned

and bandaged and get the bleeding—"

"And I need you."

"Obviously." He laughed at the

mockery in my voice. "When are we leaving?"

"Monday," he mumbled as he maneuvered

me out of the bath toward the still unmade bed. "Take off your clothes."

"Tell me what happened." I was

bargaining. Montgomery was having none of it. He pulled the damp, crimson

gauze away and with bloodied hands pulled my clothes off, pushing me down

on the mattress. His eyes met mine, and the light in them made me stop

trying to stanch the bleeding. His breathing was harsh and he bit me again,

this time on my breast, hard. I stopped struggling.

Montgomery sensed the change in me and became

gentle, tender. He looked into my eyes as he made love to me, my body

passive beneath his, his blood dripping onto my chest, my throat, into

my hair, and puddling the sheets with his exertion.

My breath came fast and hard, not from passion,

but from fear; my skin was cold and clammy, my hands and feet tingling.

Hyperventilation, some remote and rational part of my mind whispered.

Montgomery's eyes glittered with a strange, sparkling horror and laughter.

When he was done, Montgomery left me lying

on the bed and showered. I could hear the water sluicing against the tile,

thudding against Montgomery. Unmoving, I studied the molding around the

ceiling, counting the swirls and rosettes as his blood dried on me and

cracked. Carefully I kept my mind blank.

I had seen a rabid dog once, brought in

to the clinic by a distraught boy who didn't understand what the insanity

meant any more than he understood what the bites on his arms would mean

later in terms of pain and shots and fear on the part of his family. The

dog had writhed and fought and clawed once released, and I had ushered

the boy out into the waiting room while Daddy got his gun and blew the

dog's body apart. And that dog had Montgomery's eyes.

Dry and clean, his wound bandaged as well

as I might have managed and a towel wrapped around his waist, he returned,

bringing the tray to the bed. Plumping the pillows, he propped me against

them, positioning me like a doll. And ignoring the blood and the stink

of semen, he fed me.

I

ate, afraid to refuse although I wanted nothing now. And then, still without

explaining, Montgomery dressed and left, humming a little tune. The lock

clicked.

I

spent the entire weekend locked in my room. For my protection, Montgomery

said later. Because I was too innocent, too lovely, and too much of a

temptation for his brothers, and he would not share that which he chose

as his own. Share with his own brothers? Share me?

I

spent the weekend alternately furious and frightened, despondent and dejected.

I was safe in the room as long as fire didn't break out or one of the

brothers break in. But I was bored and lonely and God knows curious. Surely

this family wasn't a danger to me. Surely I had misread both the situation

and Montgomery's cryptic comments. And the rabid dog look in his eyes....

Surely. And yet....

When

Monday came, we left without good-byes, driving down the curving drive

in Miles Justin's antique T-bird, the top down and a hot wind tangling

my hair. I was so glad to be leaving that relief was a potent pulse beneath

my skin. I looked back at the old house, its windows black holes like

empty sockets in an old skull, the wisteria kinked and snarled like arthritic

fingers reaching for the cavities.

Where

just moments before, the front porch had been empty, Miles Justin now

stood, his hip casually against the banister, watching. Even through the

widening distance, his eyes met mine and he smiled. With all the grace

of the DeLandes he lifted his left hand and gripped the crown of his cowboy

hat, one finger in the central dip. He raised the hat slightly. It was

a kindness and a jest all at the same time, and I laughed as the drive

turned and the wisteria hid my enigmatic brother-in-law from view, his

hat still in the air.

I

should have known. I should have understood.

Excerpt

from the book BETRAYAL by Gwen Hunter

ęGwen Hunter

Book Signings:

Visit Gwen Hunter's website for latest info:

BETRAYAL

Author: Gwen Hunter

Publisher: Bella Rosa Books

6" x 9" Trade Paper

ISBN 0-9747685-0-2

Retail: $16.95US; 336pp

read

the first chapter

back to book details

reviews

To purchase BETRAYAL

from your local independent bookseller click here:

![]()

Purchase

at booksamillion.com:

![]()

Or you may order a

copy of BETRAYAL, signed by the author (limited supply),

direct from BellaRosaBooks using PAYPAL.

$17.00 Includes shipping & handling worldwide.

Click the button below to place your order.

BOOKSELLERS:

All Bella Rosa

Book titles are available through

Ingram, Baker & Taylor, Brodart Company, Book Wholesalers, Inc. (BWI),

The Book House, Inc., and

Parnassus distributors.

Booksellers, Schools,

and Libraries can also purchase

direct from Bella Rosa Books.

For quantity discounts contact sales@bellarosabooks.com

.