larger

view of cover

read an excerpt

buy

the book

Tamar Myers will be signing books in conjunction with the Spoleto festival

in Charleston, SC. Come see her, and get your books signed, at the Tea

Room at Grace Church, 98 Wenworth St., Charleston.

The date:

May 29th, 2006.

The time: 11:00-2:30.

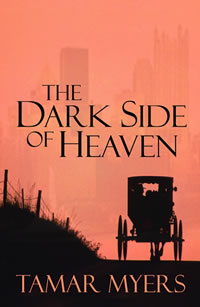

THE

DARK SIDE OF HEAVEN

Author: Tamar Myers

Original Title from Bella Rosa Books

Hardcover w/dustjacket

chapter one

I discover

the dark side of Heaven the day Bishop Yoder pronounces me dead. He pokes

my shoulder with his index finger, which is as thick and soft as a cow's

teat. Such behavior is not the Amish way, but I have provoked the elderly

man beyond human endurance.

"Anna

Hostetler," he says, "you leave me with no choice."

"You leave me with no choice,"

I say. I have been crying all morning and my throat is as rough as feed

sacks. It hurts even to swallow.

"The Elders agree with me, Anna. I must impose

the Meidung. Do you understand this?"

I nod, hoping this will keep the bishop from giving

me a long explanation. The Meidung means that I am now excommunicated,

banned from any sort of meaningful contact with my family, completely

cut off from my people. Until I confess my sin—something I cannot

do—it will be as if I am dead.

Unfortunately, a bob of the head is not going to stop Bishop Yoder. "Even

your parents may not speak to you now. If you remain at home, they will

make you eat by yourself, at one end of the table, on a special cloth.

If you are stubborn about this, and come to the Sunday service—"

I turn my back on Bishop Yoder and walk toward

the Trailways bus station. It is just a stop really, the waiting room

nothing more than a row of blue plastic chairs in Miller's Laundromat.

My legs are as unsteady as those of a foal taking her first steps, and

I long to lie down on the warm asphalt of the parking lot and nap. But

I will not show any further weakness, and I will not turn around. If I

am dead to the others, am I not dead to the bishop as well? What good

does it do to have a dead woman stay and listen? Besides, what else can

Bishop Yoder and the Elders do to me? Burn me at the stake? That is what

the Catholics did to our ancestors in Switzerland, and it is one of the

reasons we are so committed to being a people apart.

The slap-slap of leather tells me that the bishop

is following me. Perhaps he thinks he has a right. After all, it is he

who has insisted on bringing me here in his summer buggy, for all the

world to see. It is just as well that he did so. Mamm and Daat were too

heartbroken to deliver their youngest child permanently into the hands

of the English. But I have to pay a price for the ride; a lecture that

will not end, and tears. Not just my tears either, but those of Bishop

Yoder. He is truly pained by what I am forcing him to do. Of that I have

no doubt.

"Remember, Anna Hostetler, that God always

welcomes a repentant sinner. This shunning is only so that you will find

your way back to us again."

I stop walking. "Remember Bishop," I

say, without turning, "that God is also the Creator. He gave me this

gift. It would be a sin for me not to use it."

"This gift—it involves pride, yah?"

I take my time to think about that. "Not so much pride, as satisfaction.

When I paint, I am helping God to create."

"Ach, Anna, that is blasphemy."

I close my eyes, thankful that we are speaking

in dialect, known to most of the English as Pennsylvania Dutch. My mother

tongue has nothing to do with Holland, but was derived from Swiss German.

"Why else would God give me this talent?

And I do have talent—everyone says so."

"The English say so."

"Yah, and they buy my paintings. They would

not buy them if they were not good."

"But you compare yourself to God—"

I look at the Bishop. "I did not compare

myself to God." Even a year ago, I would not have dared to interrupt

the bishop. "What I meant to say, Bishop, is that by using my talent

for painting, I am honoring God."

"Yah, a good quilt—"

"My talent is not for quilting. It is for

painting!"

"Then paint barns, Anna Hostetler."

Amish culture is based on something called Gelassenheit—submission.

The individual must submit his or herself to the community and ultimately

to God. The ability to yield oneself comes more easily for some than it

does for others. For me it has always been next to impossible.

The bishop and I are both silent for a moment.

Perhaps he is waiting for me to have a change of heart. I certainly am

hoping the same for him.

Finally, he speaks. "You will go to your

brother then?"

"What good will that do? You just said he

is not allowed to talk to me, even if he wanted—which he does not,

by the way."

"Ach, not your married brother, Elam. The

brother in Pittsburgh."

I turn. "What brother in Pittsburgh?"

Bishop Yoder leans back. It is as if my words

have slapped him.

"You have never heard?"

"Heard what?"

"Your brother, the oldest one—what he

did?"

"Elam is my oldest brother," I shout.

Shouting at a bishop is surely a sin in itself. It is not just my art

that has been a stumbling block. There are a thousand other things for

which I deserve to be banished.

Bishop Yoder shakes his head. "I cannot believe

no one has told you this." He shakes his head again. "Surely

there were rumors."

"If there were, I missed them."

Neither the bishop nor I wear watches, but we

have battery-operated clocks in our homes, and we have agreed to arrive

at the bus stop early. Besides, like many other Amish sects, we set our

clocks a half hour early. Fast time, we call it. It is yet another way

we choose to separate ourselves from the world. At any rate, by my reckoning

we have another half hour to wait for the bus.

"Come." Bishop Yoder pokes me again,

even more gently this time. "It is against the Ordnung,"

he says, referring to the church's rules of behavior, "for us to

have this air-conditioning in our homes, but in the English place of washing

clothes, it is permitted for us to sit."

Carrying only a sack made from one of Mamm's old

quilts and a cardboard tube, I follow the bishop into the Laundromat,

into a new world of sights and sounds. Clothes swishing in water, because

the English are too lazy, or too much in a hurry to wash them the old

way. Clothes spinning in hot machines because the English no longer value

the scent of sunshine. And the television. I have seen television, flickering

through windows of shops, but never close up. I cannot remember ever hearing

one. This television has a black woman in it. She stands on a platform

and addresses a large gathering of people. Behind the standing woman sits

a man in a comfortable English chair. The crowd is clapping.

There is only one other person in the Laundromat,

an English woman in a sleeveless blouse and pants like a man's, only short.

She is folding clothes at a table that wobbles, and when we enter, she

looks up briefly before continuing her task. No doubt she has seen many

of our kind before about town. Our town is very small, I hear, compared

to others, and there are many other plain folk living in the area.

The bishop and I sit on the blue plastic chairs.

His chair is cracked; mine has a wad of gum in one corner. I put the cloth

sack on the floor, but the cardboard tube I balance on my knees. Even

though the bishop is old enough to be my Grossdawdi, we are careful to

keep a chair between us. Grossdawdi Hostetler is fat, with a neck burned

red by the sun, and when he was younger, he had the blackest hair I had

ever seen on an Amish man. Bishop Yoder has white curls peeking from beneath

his black felt hat, and except for his prominent Yoder nose, he has the

face of a sheep. Even his teeth are long and yellow.

I am calmer now, and the bishop seems to sense

this. I am sitting with my body straight ahead, facing the television.

The bishop is sitting in the same position, but from the corner of my

left eye I see his torso turn so that now he is looking at me. The sheep

eyes, like all sheep eyes, appear baffled.

"No one has ever spoken to you about Nathaniel?"

The black woman in the television has just asked

the man in the chair a more interesting question. She calls him Dr. Phil,

but the question she asks is not about health. How long is too

long for a man to live at home with his parents, she wants to know. Dr.

Phil says something I cannot understand, but it makes the crowd laugh.

The English woman folding clothes on the wobbly table laughs along with

the crowd.

"Ach, Anna, you cannot pretend you do not

remember Nathaniel."

"I do not." At least I do not want to.

"But you remember the fire, yah?"

"Yah," I whisper.

* * *

Fire

shaped the history of my people, my family in particular, beginning with

the pillar of fire that led the ancient Israelites through the desert.

Through Christ we are spiritual descendants of those people, are we not?

Then there were the fires of persecution in sixteenth-century Switzerland,

although there were many ways in which both church and state persecuted

my people. We, the followers of Jakob Ammann, were Anabaptists. We did

not believe in infant baptism, and rebaptized—hence our name. We

were hunted like rabbits in the field, and had to worship in secret, sometimes

in caves. When they caught us they burned us, drowned us, and even pulled

us limb from limb on stretching devices. These persecutions are written

down in the Martyrs Mirror, a book that is found in every Amish

home, and we do not forget them. We sing about them in our hymns, we tell

them to our children as bedtime stories. They are seared into our memories

like the brand on a calf.

In the late seventh century William Penn offered

us sanctuary in the New World. There were fires in Pennsylvania as well,

but not sparked by religious persecution. On the night of September 19th,

1757, a band of Delaware Indians attacked the Hochstetlers—as my

family was known then—in Northkill, Pennsylvania. We Amish are pacifists,

so although my ancestors possessed a gun, they would not turn it on another

human being. The Delaware set the cabin on fire and it burned to the ground.

There was, however, a storage cellar under the cabin, and as it was apple

harvest season, and cider had just been made, the family wet the ceiling.

They were spared the fire, but the next morning my female ancestor, whose

first name is not known, was stabbed in the back, and scalped, as she

tried to exit the cellar through a small side door.

My great-great-great-great grandfather, Jacob

Hochstetler, and two of his sons, Joseph and Christian, were captured

alive by the Delaware, and remained their prisoners for many years. From

this one ancestor, Jacob, virtually every Hochstetler and Hostetler descend.

This is also a story we tell the children. Do not forget our history,

we tell them. Remember that we are a people opposed to violence.

But the fire that occurred on my third birthday

is one that I have tried hard to forget. It is, in fact, my first memory.

In it I sit by the window that faces the barn and watch men shout encouragement

to each other as they try in vain to put out the flames. There are women

helping too, passing buckets of water down a line that leads from the

pump by the kitchen door, but there are no children. I am the only child,

and I am safe inside. Where are the others?

There is another pump closer to the barn, the

one Daat uses to fill the water troughs, but no one is using it. Even

here, I can feel the heat from the barn through the glass. The frost on

the pane has melted and there are rivulets of water running down onto

the sill.

I trace the barn in the condensation. I trace

the flames leaping from the roof. I trace the men and women in the bucket

line. That is my first memory of drawing. Suddenly the barn collapses,

sending sparks all the way into the sky, burning the feet of angels. A

few of the women scream, a man shouts louder, and then everyone is inside.

But still no children. This memory starts to fade, when a woman, whose

face I can not remember, snatches me away from the window and carries

me upstairs to bed.

* * *

"How

well do you remember the fire?" the bishop asks.

"Very well. It was Daat's barn that burned,

yah?"

"Yah." The bishop sounds so sad I want to

reach across the plastic chair between us and touch him, maybe put my

hand on his. Of course that is impossible. Only a misfit like myself would

think of such a thing.

Neither of us says anything for a moment. In the

meantime the lady with no sleeves stops folding to watch the black woman

in the television. The black woman is waving her arms and saying that

if anyone ever did that to her, well, she'd never invite them into

her home again. The man in the chair agrees and the crowd claps.

"That is the day I started drawing,"

I say. How stupid of me. I only say this because I know the bishop is

trying hard not to watch the television.

Bishop Yoder winces. "Anna, soon the bus

will come, but first there are things I must tell you."

I nod to signify that I am listening.

He sucks in his breath, like he is slurping hot

soup. Before he can speak, the woman without sleeves shuts down the television

and approaches. She stops when she is so close that I can see that her

legs are entirely without hair.

"Youse two waiting for the bus?" she

asks in a voice as high and sharp as a bluejay's.

"Yah, me," I say. "I go to Pittsburgh."

"Got a ticket?"

"No. I can buy one on the bus, yah?"

"Used to be," she chirps. "But

now ya gotta buy it from me. I'm the local agent. Ya wanna leave Heaven,

ya gotta do it by me." She laughs. Heaven is the name of the town.

I am told it is the only Heaven in Pennsylvania. English tourists love

this name, and our sign is many times stolen.

"How much?" I have lots of money. In

fact, in the quilt sack at my feet I have almost a thousand dollars—exactly

nine hundred eighty—that I got for one of my paintings to an English

tourist. It was the painting I called The Wedding. In it all the

women wear black, including the bride, but she wears a white apron as

well. Everyone is smiling, except for the bride.

Faces. Painting faces was on my list of sins.

A picture with a face is like a statue, which in turn is like an idol.

Even our dolls do not have faces.

"Pittsburgh is fifty-nine dollars plus tax."

"So much?' The bishop asks. He looks alarmed.

"Ya can fly from Harrisburg," she says.

"But it won't be any cheaper. Youse allowed to fly?"

Bishop Yoder rises to his feet. "It is better

to take the bus."

Amish people are allowed to fly, but only under

special circumstances, usually health related. It is the last choice.

Although my people are not allowed to own cars, it is permissible to accept

rides from Mennonites, our worldly cousins. Sometimes we even hire them

to take us places that are too far to reach by a buggy in a day's drive.

Of course now that I am dead, what difference does it make how I leave

Heaven? Although I know there are those who think I have already fallen

from Heaven, like Lucifer. Catherine Beiler, our neighbor, is one of those.

"Than ya better fork it over," the bird

woman says, "because I hear the bus coming now."

I jump to my feet. Bishop Yoder has yet to tell

me about this Nathaniel, the one who is supposed to be my brother. The

bus stops in Heaven every day but Sunday, and today is Wednesday. There

is a small hotel just down the street. Surely I have enough money to stay

there one night.

"Well, ya going, or not?"

"I am going," I say. But I have never

been so frightened. Excited too. I have never ridden in a bus. I have

never ridden in a Mennonite car. In fact, I have never ridden in anything

that was not pulled by a horse.

"It won't wait, ya know."

I grab my quilt sack from the floor and open it,

looking for the money. Before I can find it, the bus pulls beside the

Laundromat. I have seen buses before, but none so large. This one also

makes the most noise, more noise even than the generator Jonathan Berkey

bought for his dairy, and which the bishop made him return.

"Ya better hurry," the agent says. "He

only stops a minute. If there aren't any passengers, I'm to wave him on."

I find the money and give her three twenty dollar

bills.

"The tax."

I give her another twenty. She searches in the

pockets of her man's shorts for the change.

In the meantime the bus door opens and three people

get off. Two of them are men, and they immediately light cigarettes. They

light them as they climb down the steps. The third person to get off is

a young woman about my age. She heads straight inside.

"Where's the john?" she yells. She acts

like she is talking to no one in particular, but I know she has seen us.

Her eyes are as big as buggy wheels.

"That way," the agent grunts, and using

the back of her head, points to a corner.

The young woman runs to the rear of the Laundromat.

I am still putting my change into the quilt sack when she runs past us

again. She is out of breath, but she can speak.

"When you gotta go, you gotta go, and I ain't

peeing on no damn bus, that's for sure." The words trail behind her

like smoke from a chimney.

Bishop Yoder's pale face turns deep pink. "Anna,"

he says, "you can—"

The bus honks so loud I drop the quilt sack, but

not the cardboard tube.

"Go," the bishop says.

This time I obey.

copyright © 2006 Tamar Myers

THE

DARK SIDE OF HEAVEN

Author: Tamar Myers

Bella Rosa Books Original Title

Hardcover w/dustjacket

$25.00US; 312pp

ISBN

1-933523-01-8

LCCN 2005934404

read

an excerpt

buy the book

To purchase from your

local independent bookseller click here:

![]()

Purchase

at booksamillion.com:

![]()

You may pre-order

direct from BellaRosaBooks using PAYPAL.

$25.00 Includes shipping & handling worldwide.

Click the button below to begin the order process.

Or, you may contact us at sales@bellarosabooks.com for details.

BOOKSELLERS:

All Bella Rosa

Book titles are available through

Ingram, Baker & Taylor, and Parnassus distributors.

Schools and Libraries may order through

Brodart Company or Book Wholesalers, Inc. (BWI).

Booksellers, Schools,

and Libraries can also purchase

direct from Bella Rosa Books.

For quantity discounts contact sales@bellarosabooks.com

.